4 Oocyte Maturation, Ovulation and Fertilization

Oocyte maturation takes place in the oocyte closest to the spermatheca, just before ovulation, and is stimulated by sperm-derived major sperm protein (MSP) (GermFIG 5) (Miller et al., 2001). During maturation, nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD; also known as germinal vesicle breakdown) occurs, the nucleus becomes less obvious, and cortical rearrangements cause the oocyte to become more spherical. Chromosome arrangement changes as bivalent chromosomes leave diakinesis and begin to align onto the metaphase plate (Ward and Carrel, 1979; McCarter et al., 1999).

GermFIG 5: Major sperm protein (MSP) promotes oocyte maturation and ovulation. Events triggered by MSP and the maturing oocyte, in their approximate order, are indicated with numbers. (Sp) Spermatheca. (Based on Miller et al., 2001, 2003.)

Ovulation follows oocyte maturation. Signals from the maturing oocyte and MSP stimulate the rate and intensity of sheath contraction from a basal rate of 10–13 contractions/minute to approximately 19 contractions/minute (McCarter et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2001, 2003). Oocyte maturation also stimulates distal spermathecal dilation through LIN-3/LET-23 RTK pathway activation and IP3 signaling (Clandinin et al., 1998; McCarter et al., 1999; Bui and Sternberg, 2002). The dilated spermatheca is pulled over the oocyte by the contracting sheath, and the spermatheca then closes. The oocyte is immediately penetrated by a sperm and fertilized. Cell–cell recognition between gametes during this process is mediated by SPE-9, a sperm-specific, epidermal growth factor (EGF)-repeat-containing transmembrane protein (Singson et al., 1998). Cytoplasmic streaming in the oocyte accompanies fertilization, meiosis is completed, and eggshell secretion commences (Ward and Carrel, 1979; Singson, 2001). The newly formed embryo then passes from the spermatheca to the uterus via the spermathecal-uterine valve.

5 Germ-line Development

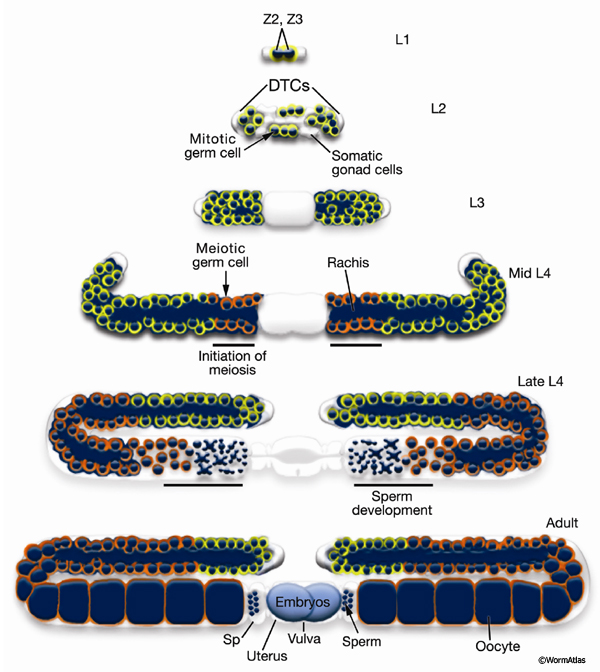

Germ-line development spans L1 to early adulthood (GermFIG 6; GermMOVIE 1). All germ cells are descended from either Z2 or Z3 (Schedl, 1997; Hubbard and Greenstein, 2000). In contrast to somatic lineage development, germ-line cell divisions appear to be variable with respect to their timing and planes of division, and hence the precise lineal relationships between these cells are not known (Kimble and Hirsh, 1979). In L4, approximately 37 meiotic cells per arm at the most proximal end of the germ line commit to sperm development. Subsequently, the germ line switches from making sperm to making oocytes for the remainder of development and throughout adulthood. This switch between male and female cell fate results from germ-line modulation of sex determination pathway activity (Kuwabara and Perry, 2001). Germ-line development depends on interactions with the overlying somatic gonad. Somatic gonad cells, or their precursors, affect the timing and position of the germ-line mitosis/meiosis decision, and they exit from pachytene, gametogenesis, and male gamete fate during germ-line sex determination (Kimble and White, 1981; Seydoux et al., 1990; McCarter et al., 1997; Rose et al., 1997; Pepper et al., 2003; Killian and Hubbard, 2004).

GermMOVIE 1: Animation of hermaphrodite gonadogenesis. Click on animation to open movie. Press "Play" to start,"Pause" to stop or click boxes to view specific stages. Note, movie does not follow the color code used in GermFIG 6 above. Yellow, germ nuclei; Red , DTC nuclei; Purple, other early somatic cell nuclei. As germline development proceeds, mitotic nuclei remain yellow, while green represents meiotic stages (light green for early stages [leptotene and zygotene] and darker for later stages [pachytene]). Blue, spermatocytes; Dark Blue, mature sperm; Pink, oocytes. Note: only one gonad arm is depicted but the other develops in the same way. (Image source: E. J. Hubbard. Animation by Rob Stupay © 2003.)

6 Spermatogenesis and Spermiogenesis

See Sperm Gallery for detailed pictures and videos

The germ line of each gonad arm produces about 150 sperm during L4 (GermFIG 6 and GermFIG 7A) (L’Hernault, 1997). Approximately 37 diploid germ cells per gonad arm form primary spermatocytes while still attached to the rachis. After pachytene, spermatocytes detach from the rachis and complete meiosis, generating haploid spermatids. This process of spermatid formation is called spermatogenesis (GermFIG 7B, C&D) (Ward et al., 1981).

GermFIG 7A: Sperm development. Top Schematic showing stages of sperm (spermatozoa) development. Middle Intracellular events associated with each step. Bottom Steps that correspond to spermatogenesis or spermiogenesis. (Based on L'Hernault 1997.)

GermFIG 7B: Spermatogenesis. DIC view of a late-L4 hermaphrodite proximal gonad arm (before first ovulation) showing male gametes at various stages of spermatogenesis within the gonadal sheath. (DG) Distal gonad; (Sp) spermatheca. Magnification, 400x.

GermFIG 7C&D: Spermatogenesis. TEM, transverse sections of a late-L4 hermaphrodite at the axial positions indicated in B. (Image source: Hall archive.)

Developing spermatocytes contain a large number of specialized vesicles called fibrous body-membranous organelles (FB-MOs) (GermFIG8 A&B and GermFIG 9A). These organelles contain proteins required in the future spermatids and spermatozoa, including MSP (Ward and Klass, 1982). During development, the FB-MOs partition with the portion of the spermatocyte destined to become the future spermatid (Ward, 1986). The residual body (GermFIG 7B&7D, Budding Spermatids Figure) acts as a deposit area for proteins and organelles no longer required by the developing spermatid (L’Hernault, 1997; Arduengo et al., 1998; Kelleher et al., 2000).

GermFIG 8: Development of fibrous body–membranous organelles (FB-MOs) during spermiogenesis. A. Top Schematic showing the steps of FB-MO formation with stages of increasing maturation from right to left. Below Corresponding stage of sperm development in which the event occurs. B. Organization of a single FB-MO.

GermFIG 9: Electron micrographs of FB-MOs. A. TEM, transverse section, of a late-L4 hermaphrodite (before first ovulation), showing FB-MOs beginning to assemble in a primary spermatocyte. (N) Nucleus. (Image source: N506 [Hall] Y810.) B. TEM, transverse section, from a more proximal region of the animal in A, showing spermatids containing late-stage MOs, devoid of FB and collecting at the cell membrane. (N) Nucleus. (Image source: N506 [Hall] Y858.) C. TEM, transverse section, of a spermatozoon showing a pore formed by fusion of an MO with the cell membrane. (M) Mitochondria. (Image source: [Hall] H707.)

Spermatogenesis takes place within the proximal gonad (GermFIG 7B). The formed spermatids are pushed into the spermatheca by the first oocyte during the first ovulation. In the spermatheca, an unknown signal induces these sessile spermatids to undergo morphogenesis into mature, amoeboid spermatozoa (sperm) (cf. GermFIG 9B&C, Spermatozoon SEM and TEM) (Nelson and Ward, 1980; Ward et al., 1983). This process of activation is known as spermiogenesis (See Spermiogenesis Figure and Video in Sperm Gallery).

Maturing spermatids and spermatozoa have highly condensed nuclei and tightly packed mitochondria (GermFIG 9B&C, Spermatozoon TEM Figure). In spermatids, MOs (now lacking the FB) locate near the cell periphery (GermFIG 9B). During spermatid activation, MOs fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing their contents (primarily glycoproteins) onto the cell surface. A fusion pore is generated on the cell surface by the MO collar (GermFIG 9C). Mutants affected in MO fusion produce sperm with defective motility, suggesting that MO content enhances sperm mobility (Ward et al., 1981; Roberts et al., 1986; Achanzar and Ward, 1997). Unlike sperm in many other animal phyla, C. elegans sperm are not flagellated. Rather, spermatid activation involves the formation of a foot or pseudopodium that allows the spermatozoon to attach to the walls of the spermathecal lumen and to crawl by projecting from and dragging the cell body (see Sperm Crawling and Treadmilling Videos). This motility is driven by dynamic polymerization of MSP, which, in addition to containing sequences that mediate extracellular signaling (described above; Miller et al., 2001), has an intracellular cytoskeletal function (Italiano et al., 1996; Roberts and Stewart, 2000).

7 References

Achanzar, W.E. and Ward, S. 1997. A nematode gene required for sperm vesicle fusion. J. Cell Sci. 110: 1073-1081. Article

Arduengo, P.M., Appleberry, O.K., Chuang, P. and L'Hernault, S.W. 1998. The presenilin protein family member SPE-4 localizes to an ER/Golgi derived organelle and is required for proper cytoplasmic partitioning during Caenorhabditis elegans spermatogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 111: 3645-3654. Article

Bui, Y.K. and Sternberg, P.W. 2002. Caenorhabditis elegans inositol 5-phosphatase homolog negatively regulates inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate signaling in ovulation. Mol. Biol. Cell 13: 1641-1651. Article

Church, D.L., Guan, K.L. and Lambie, E.J. 1995. Three genes of the MAP kinase cascade, mek-2, mpk-1/sur-1 and let-60 ras, are required for meiotic cell cycle progression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 121: 2525-2535. Article

Clandinin, T.R., DeModena, J.A. and Sternberg, P.W. 1998. Inositol trisphosphate mediates a RAS-independent response to LET-23 receptor tyrosine kinase activation in C. elegans. Cell 92: 523-533. Article

Crittenden, S.L., Troemel, E.R. Evans, T.C. and Kimble J. 1994. GLP-1 is localized to the mitotic region of the C. elegans germ line. Development 120: 2901-2911. Article

Grant, B. and Hirsh, D. 1999. Receptor-mediated endocytosis in the Caenorhabditis elegans oocyte. Mol .Biol. Cell. 10: 4311-4326. Article

Gumienny, T.L., Lambie, E., Hartwieg, E., Horvitz, H.R. and Hengartner, M.O. 1999. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodite germline. Development 126: 1011-1022. Article

Hall, D.H., Winfrey, V. P., Blaeuer, G., Hoffman, L.H., Furuta, T., Rose, K.L., Hobert, O. and Greenstein, D. 1999. Ultrastructural features of the adult hermaphrodite gonad of Caenorhabditis elegans: relations between the germ line and soma. Dev.. Biol. 212: 101-123. Article

Hansen, D., Wilson-Berry, L., Dang, T. and Schedl, T. 2004. Control of the proliferation versus meiotic development decision in the C. elegans germline through regulation of GLD-1 protein accumulation. Development 131: 93-104. Article

Hengartner, M.O. 1997. Apoptosis and the shape of death. Dev. Genet. 21: 245-248. Abstract

Hengartner, M.O., Ellis, R.E. and Horvitz, H. R. 1992. Caenorhabditis elegans gene ced-9 protects cells from programmed cell death. Nature 356: 494-499. Abstract

Hirsh, D., Oppenheim, D. and Klass, M. 1976. Development of the reproductive system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 49: 200-219. Abstract

Hubbard, E.J. and Greenstein D. 2000. The Caenorhabditis elegans gonad: a test tube for cell and developmental biology. Dev. Dyn. 218: 2-22. Article

Italiano, J.E. Jr., Roberts, T.M., Stewart, M. and Fontana, C.A. 1996. Reconstitution in vitro of the motile apparatus from the amoeboid sperm of Ascaris shows that filament assembly and bundling move membranes. Cell 84: 105-114. Article

Kelleher, J.F., Mandell, M.A., Moulder, G., Hill, K.L., L'Hernault, S.W., Barstead, R. and Titus, M.A. 2000. Myosin VI is required for asymmetric segregation of cellular components during C. elegans spermatogenesis. Curr. Biol. 10: 1489-1496. Article

Killian, D.J. and Hubbard, E.J. 2004. C. elegans pro-1 activity is required for soma/germline interactions that influence proliferation and differentiation in the germ line. Development 131: 1267-1278. Article

Kimble, J.E. and Hirsh, D. 1979. The postembryonic cell lineages of the hermaphrodite and male gonads in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 70: 396-417. Article

Kimble, J.E. and White, J.G. 1981. On the control of germ cell development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 81: 208-219. Abstract

Kuwabara, P.E. and Perry, M.D. 2001. It ain't over till it's ova: germline sex determination in C. elegans. Bioessays 23: 596-604. Abstract

L'Hernault, S. W. 1997. Spermatogenesis. In C. elegans II (ed. D. L. Riddle et al.). chap. 11. pp. 417-500. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York. Article

McCarter, J., Bartlett, B., Dang, T. and Schedl, T. 1997. Soma-germ cell interactions in Caenorhabditis elegans: multiple events of hermaphrodite germline development require the somatic sheath and spermathecal lineages. Dev. Biol. 181: 121-143. Article

McCarter, J., Bartlett, B., Dang, T. and Schedl, T. 1999. On the control of oocyte meiotic maturation and ovulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 205: 111-128. Article

Miller, M.A., Nguyen, V.Q., Lee, M.H., Kosinski, M., Schedl, T., Caprioli, R.M. and Greenstein, D. 2001. A sperm cytoskeletal protein that signals oocyte meiotic maturation and ovulation. Science 291: 2144-2147. Abstract

Miller, M.A., Ruest, P.J., Kosinski, M., Hanks, S.K. and Greenstein, D. 2003. An Eph receptor sperm-sensing control mechanism for oocyte meiotic maturation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 17: 187-200. Article

Nelson, G.A. and Ward, S. 1980. Vesicle fusion, pseudopod extension and amoeboid motility are induced in nematode spermatids by the ionophore monensin. Cell 19: 457-464. Abstract

Pepper, A.S., Lo, T.W., Killian, D.J., Hall, D.H. and Hubbard, E.J. 2003. The establishment of Caenorhabditis elegans germline pattern is controlled by overlapping proximal and distal somatic gonad signals. Dev. Biol. 259: 336-350. Article

Roberts, T.M. and Stewart, M. 2000. Acting like actin. The dynamics of the nematode major sperm protein (msp) cytoskeleton indicate a push-pull mechanism for amoeboid cell motility. J. Cell Biol. 149: 7-12. Article

Roberts, T.M., Pavalko, F.M. and Ward, S. 1986. Membrane and cytoplasmic proteins are transported in the same organelle complex during nematode spermatogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 102: 1787-1796. Article

Rose, K.L., Winfrey, V.P., Hoffman, L.H., Hall, D.H., Furuta, T. and Greenstein D. 1997. The POU gene ceh-18 promotes gonadal sheath cell differentiation and function required for meiotic maturation and ovulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 192: 59-77. Article

Schedl, T. 1997. Developmental Genetics of the Germ Line. In C. elegans II (ed. D. L. Riddle et al.). chap. 10. pp. 417-500. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York. Article

Seydoux, G., Schedl, T. and Greenwald, I. 1990. Cell-cell interactions prevent a potential inductive interaction between soma and germline in C. elegans. Cell 61: 939-951. Abstract

Singson, A. 2001. Every sperm is sacred: fertilization in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 230: 101-109. Article

Singson, A., Mercer, K.B. and L'Hernault, S.W. 1998. The C. elegans spe-9 gene encodes a sperm transmembrane protein that contains EGF-like repeats and is required for fertilization. Cell 93: 71-79. Article

Vogel, B.E. and Hedgecock, E.M. 2001. Hemicentin, a conserved extracellular member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, organizes epithelial and other cell attachments into oriented line-shaped junctions. Development 128: 883-894. Article

Ward, S. 1986. Asymmetric localization of gene products during the development of C. elegans spermatozoa. In Gametogenesis and the Early Embryo. (ed. J. G. Gall). pp. 55-75. 44th Symposium of the Society for Developmental Biology. Alan R. Liss, New York.

Ward, S. and Carrel, J.S. 1979. Fertilization and sperm competition in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 73: 304-321. Abstract

Ward, S. and Klass, M. 1982. The location of the major protein in Caenorhabditis elegans sperm and spermatocytes. Dev. Biol. 92: 203-208. Abstract

Ward, S., Argon, Y. and Nelson, G.A. 1981. Sperm morphogenesis in wild-type and fertilization-defective mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Biol. 91: 26-44. Article

Ward, S., Hogan, E. and Nelson, G.A. 1983. The initiation of spermiogenesis in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 98: 70-79. Abstract

|